I believe this is what began the climax of the battle, some time around 4:00pm, 25 June, 1876. After pausing briefly at the bottom of the Medicine Trail Coulee and Long Coulee, head of scouts Mitch Bouyer, Lieutenant George Armstrong Custer and German born "C" company bugler Henry Dose, all entered the stream together at the Minniconjou Ford (above). Just about half way across, Dose was shot and killed by the Cheyenne warrior Bobtail Horse. At almost the same moment, White Bull, a Sioux warrior, shot Custer. Wounded in his chest, "Yellow Hair" fell into the river.

According to several witnesses who helped recover Custer's body two days after the battle, Custer had received a gunshot wound in his left chest "near the heart". Assuming the bullet missed the heart, it would have caused a massive spontaneous pneumothorax - damaging his rib cage before puncturing the upper lobe of his left lung and leaving behind a sucking chest wound. Air and blood filled the chest space outside his now deflated lung (above) causing intense pain, rapid and continuing blood loss and the inability to draw a deep breath. Custer was probably conscious, but would be unable to communicate coherently.

Captain Myles Walter Keogh (above) leading Companies C, I and L, might have tried to organize a defense on the river bank, just to slow any attempt to follow the wounded Custer. But there was little time.

Captain George Yates (above) was in command of companies E and F, farthest behind the head of the column.

Working the lever on his Winchester rifle White Bull loaded another round and shot Boyar. Wounded, the Frenchman fell into the river. Later, he was able to pull himself into the shallows on the Indian side of the river, but was discovered there by warriors, who recognized him as a traitor to his Sioux family, murdered him and threw his body into the river.

The man in the buckskin jacket seemed to be the leader of these soldiers, for he shouted something and they all came charging at us across the ford. Bobtail Horse fired first, and I saw a soldier on a gray horse (not the flag carrier) fall out of his saddle into the water. The other soldiers were shooting at us now. The man who seemed to be the soldier chief was firing his heavy rifle fast. I aimed my repeater at him and fired. I saw him fall out of his saddle and hit the water.

T. [Note: the "three Indians that looked like Crows" were White Man Runs Him, Goes Ahead and Hairy Moccasin. Here are Goes Ahead and Hairy Moccasin's description of the exact same moment in the battle.] Bobtail Horse said:

"They are our enemies, guiding the soldiers here."

He fired his muzzleloader at them, then squatted behind the ridge to reload. I fired at them too, for I saw they were shooting at the five Sioux warriors, who were now splashing across the ford at a dead run. [Note: the "five Sioux warriors" may be a reference to the decoy / scouts that Crazy Horse scrambled when he learned from Fast Horn that Custer's troops were approaching on the morning of June 25, 1876. Foolish Elk described the exact same scene -- with Custer's men coming in hot pursuit of a handful of Indians -- but he said the decoys were Cheyenne.] My rifle was a repeater, so I kept firing at the Crows until these Sioux were safely on our side of the river. They had no guns, just lances and bows and arrows. But they got off their ponies and joined us behind the ridge. Just then I saw a Shahiyela named White Shield, armed with bow and arrows, come riding downriver. He was alone, but we were glad to have another fighting man with us. That made ten of us to defend the ford.

I looked across the ford and saw that the soldiers had stopped at the edge of the river. [Note: this agrees with Peter Thompson, who said Custer briefly halted his men at the ford while he rode upriver alone about 1,000 feet, either to scout a better place to cross or to rape the Sioux squaw Curley had waiting there.] I had never seen white soldiers before, so I remember thinking how pink and hairy they looked. One white man had little hairs on his face [a mustache] and was wearing a big hat and a buckskin jacket. He was riding a fine looking big horse, a sorrel with a blazed face and four white stockings. [Note: Although there were several officers in buckskin that day, Custer was the only one on a sorel horse with four white socks. The one detail that doesn't agree with Peter Thompson's account is that Thompson said Custer had taken his jacket off.] On one side of him was a soldier carrying a flag and riding a gray horse, and on the other was a small man on a dark horse. This small man didn't look much like a white man to me, so I gave the man in the buckskin jacket my attention. [Note: According to Pretty Shield, the "small dark man" was Mitch Bouyer, head of scouts.] He was looking straight at us across the river. Bobtail Horse told us all to stay hidden so this man couldn't see how few of us there really were.

The man in the buckskin jacket seemed to be the leader of these soldiers, for he shouted something and they all came charging at us across the ford. Bobtail Horse fired first, and I saw a soldier on a gray horse (not the flag carrier) fall out of his saddle into the water. The other soldiers were shooting at us now. The man who seemed to be the soldier chief was firing his heavy rifle fast. I aimed my repeater at him and fired. I saw him fall out of his saddle and hit the water. [Note: Seventh Cavalry scout Curley described seeing the same incident, and Pretty Shield confirmed that Custer was shot out of the saddle at the very outset of the Custer fight. See Who Killed Custer - The Eye-witness Answer for more info.]

Shooting that man stopped the soldiers from charging on. They all reined up their horses and gathered around where he had fallen. I fired again, aiming this time at the soldier with the flag. I saw him go down as another soldier grabbed the flag out of his hands. By this time the air was getting thick with gunsmoke and it was hard to see just what happened. The soldiers were firing again and again, so we were kept busy dodging bullets that kicked up dust all around. When it cleared a little, I saw the soldiers do a strange thing. Some of them got off their horses in the ford and seemed to be dragging something out of the water, while other soldiers still on horseback kept shooting at us.

I spent most of my time with the Shahiyela since I knew their tongue and their ways almost as well as my own. In all those years I had never taken a wife, although I had had many women. One woman I wanted was a pretty young Shahiyela named Monahseetah [Mona Setah], or Meotxi as I called her. She was in her middle twenties but had never married any man of her tribe. Some of my Shahiyela friends said she was from the southern branch of their tribe, just visiting up north, and they said no Shahiyela could marry her because she had a seven-year-old son born out of wedlock and that tribal law forbade her getting married. They said the boy's father had been a white soldier chief named Long Hair [George A. Custer, or more probably, his younger brother, Capt. Thomas Custer, sarcastically called Little Hair by the Sioux]; he had killed her father, Chief Black Kettle, in a battle in the south [Washita Massacre] eight winters before, they said, and captured her. He had told her he wanted to make her his second wife, and so he had her. But after while his first wife, a white woman, found her out and made him let her go.

"Was this boy still with her here?" I asked him.

I saw him often around the Shahiyela camp. He was named Yellow Bird and he had light streaks in his hair. He was always with his mother in the daytime, so I would have to wait until night to try to talk to her alone. She knew I wanted to walk with her under a courting blanket and make her my wile. But she would only talk with me through the tepee cover and never came outside....

As usual, he carried his seventeen-shot Winchester and wore two filled cartridge belts. It was very dry and dusty with little wind, and his horses were restless, for the flies were a plague on the Little Big Horn that summer.

Said White Bull, “Then the Indians charged them. They used war clubs and gun barrels, shooting arrows into them, riding them down. It was like a buffalo hunt. The soldiers offered no resistance. I saw one soldier on a gray horse, aimed at him and fired, but missed. Just then I heard someone behind me yelling that soldiers were coming from the east [Custer’s force] to attack the north end of the camp where I had left my ponies. We all raced downstream together. Some rode through the camps and crossed the river north of them, but I and many others crossed and rode up a gully to strike the soldiers on the flank. Alter a while I could see five bunches of soldiers trotting along the bluffs. I knew it would be a big fight. I stopped, unsaddled my horse, and stripped off my leggings, so that I could fight better. By the time I was near enough to shoot at the soldiers, they seemed to form four groups, heading northwest along the ridge.

“All the Indians were shooting. I saw two soldiers fall from their horses. The soldiers fired back at us from the saddle. They shot so well that some of us retreated to the south, driven out of the ravine. Soon after, the soldiers halted and some got off their horses. By that time the Indians were all around the soldiers, but most of them were between the soldiers and the river, trying to defend the camp and the ford. Several little bunches of Indians took cover where they could, and kept firing at the white men.

“When they ran me out of the ravine I rode south and worked my way over to the east ot the mounted bunch of soldiers. Crazy Horse was there with a party of warriors and I joined them. The Indians kept gathering, more and more, around this last bunch of soldiers. These mounted soldiers kept falling back along the ridge, trying to reach the rest of the soldiers who were fighting on foot.

“When I saw the soldiers retreating, I whipped up my pony, and hugging his neck, dashed across between the two troops. The soldiers shot at me but missed me. I circled back to my friends. I thought I would do it again. I yelled, ‘This time I will not turn back,’ and charged at a run the soldiers of the last company. Many of the Sioux joined my charge and this seemed to break the courage of those soldiers. They all ran, every man for himself, some afoot and some on horseback, to reach their comrades on the other side. All the Indians were shooting.

At the Battle of the Little Bighorn, June 25-26, 1876, White Bull was 26 years old. He played a very active role in the battle. In the fight White Bull counted seven coups, six of them 'firsts,' killed two men in hand-to-hand combat, captured two guns and twelve horses, had his horse shot from under him, and was wounded in the ankle by a spent bullet.

The Shahiyela [Cheyenne] camp was farthest north. We Oglala were camped just southeast of them, with the Brule in a smaller circle next to us. Next were the Sans Arc, then the Miniconjou, the Blackfoot Sioux, and farthest south next to the river were the Hunkpapa. I was twenty-eight years old that summer.

Later interviews corroborated the old Oglala's statement that Monahseetah and Yellow Bird had been in the Little Bighorn camp at the time of the fight, many of my Cheyenne informants insisting that their strict moral code, more rigid than that of the Sioux, imposed restrictions on their relationships with fallen women. I was already familiar with various accounts of Custer s winter campaign against the Southern Cheyenne in 1868, in several of which Monahseetah is mentioned as having served Custer as an interpreter -

That morning many of the Oglalas were sleeping late. The night before, we held a scalp dance to celebrate the victory over Gray Fox [General Crook] on the Rosebud a week before. I woke up hungry and went to a nearby tepee to ask an old woman for food. As I ate, she said:

"Today attackers are coming."

"How do you know, Grandmother?" I asked her, but she would say nothing more about it.

After I finished eating I caught my best pony, an iron-gray gelding, and rode over to the Cheyenne camp circle. I looked all over for Meotzi and finally saw her carrying firewood up from the river. The boy was with her, so I just smiled and said nothing. I rode on to visit with my Shahiyela friend Roan Bear. He was a Fox warrior, belonging to one of that tribe's soldier societies, and was on guard duty that morning. He was stationed by the Shahiyela medicine tepee in which the tribe kept their Sacred Buffalo Head. We settled down to telling each other some of our brave deeds in the past. The morning went by quickly, for an Elk warrior named Bobtail Horse joined us to tell us stories about his chief, Dull Knife, who was not there that day.

The first we knew of any attack was after midday, when we saw dust and heard shooting way to the south near the Hunkpapa camp circle.

Just then an Oglala came riding into the circle at a gallop.

"Soldiers are coming!" he shouted in Sioux. "Many white men are attacking!"

I put this into a shout of Shahiyela words so they would know. I saw the Shahiyela chief, Two Moon, run into camp from the river, leading three or four horses. He hurried toward his tepee, yelling:

"Natskaveho! White soldiers are coming! Everybody run for your horses!"

"Hay-ay! Hay-ay!" The Shahiyela warriors shouted their war cry, waiting in a big band for Two Moon to lead them into battle.

"Warriors, don't run away if the soldiers charge you," he told them. "Stand and fight them. Watch me. I'll stand even if I am sure to be killed!"

It was a brave-up talk to make them strong in their fight. Two Moon led them out at a gallop...

After Two Moon's band left to fight Major Reno, a new threat developed from Custer's detachment advancing down Medicine Tail coulee toward the river and the Cheyenne camp.

They're coming this way!" Bobtail Horse shouted. "Across the ford! We must stop them!"

We saw the soldiers in the coulee were getting closer and closer to the ford, so we trotted out to meet them. An old Shahiyela named Mad Wolf, riding a rack-of-bones horse, tried to stop us, saying:

Suddenly we heard war cries behind us. I looked back and saw hundreds of Lakotas [Sioux) and Shahiyela warriors charging toward us. They must have driven away those other soldiers who had attacked the Hunkpapa camp circle and now were racing to help us drive off these attackers. The soldiers must have seen them too, for they fell back to the far bank of the river, and those still on horseback got off to fight on foot. As warriors rode up to join us at the ridge a big cry went up.

"Hoka hey!" the Lakotas were shouting. "They are going!"

I saw this was true. The soldiers were running back up the coulee and swarming out over the higher ground to the north. Bobtail Horse ran to his pony, shouting to us as we caught our ponies.

"Come on! They are running! Hurry!"

He and I led the massed warriors across the ford, for the others knew we had stood bravely to protect the village and willingly followed us.

Another warrior named Yellow Nose, a Sapawicasa [Ute] who had been captured as a boy by the Shahiyela and had grown up with them, was very brave that day. After we chased the soldiers back from the ford, he galloped out in front of us and got very close to them, then raced back to safety.

e called Curley, Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin and me

Ashishishe (c. 1856–1923), known as Curly (or Curley) and Bull Half White, born in approximately 1856 in Montana Territory,

"Royal Family", Tom Custer, Co. C, Tom Calhoun, B-in-L, First Lieutenant, Co. L, Brother Boston Custer, foriger, Armstrong Reed, Nephew, guide,

I arrived at the crest of the hill without even a scratch. Here I came upon Captain French with about twenty of the men, and I joined them. Capt. French was as "cool as a cucumber" throughout the entire battle, and although I searched his face care fully for any sign of fear, it was not there. He had such perfect self-control that I had to admire his courage and bravery, and was indeed glad to be under his leadership. I was, however, considerably worried about the rest of the command, and where Custer was and why he had failed to support us as he had promised to do. It looked to me as if we would be wiped out before any assistance arrived, as the Indians were now swarming up the bluffs after us, seeking places of advantage where they could completely surround us....

George Herendon served as a scout for the Seventh Cavalry attached to Major Reno's command. After the battle, Herendon told his story to a reporter from the New York Herald Tribune (July, 1876)...We stayed in the bush about three hours, and I could hear heavy firing below in the river, apparently about two miles distant. I did not know who it was, but knew the Indians were fighting some of our men, and learned afterward it was Custer's command. Nearly all the Indians in the upper part of the valley drew off down the river, and the fight with Custer lasted about one hour, when the heavy firing ceased. When the shooting below began to die away I said to the boys 'come, now is the time to get out.' Most of them did not go, but waited for night. I told them the Indians would come back and we had better be off at once. Eleven of the thirteen said they would go, but two stayed behind.

I deployed the men as skirmishers and we moved forward on foot toward the river. When we had got nearly to the river we met five Indians on ponies, and they fired on us. I returned the fire and the Indians broke and we then forded the river, the water being heart deep. We finally got over, wounded men and all, and headed for Reno's command which I could see drawn up on the bluffs along the river about a mile off. We reached Reno in safety.

We had not been with Reno more than fifteen minutes when I saw the Indians coming up the valley from Custer's fight. Reno was then moving his whole command down the ridge toward Custer. The Indians crossed the river below Reno and swarmed up the bluff on all sides. After skirmishing with them Reno went back to his old position which was on one of the highest fronts along the bluffs. It was now about five o'clock, and the fight lasted until it was too dark to see to shoot.

As soon as it was dark Reno took the packs and saddles off the mules and horses and made breast works of them. He also dragged the dead horses and mules on the line and sheltered the men behind them. Some of the men dug rifle pits with their butcher knives and all slept on their arms.

At the peep of day the Indians opened a heavy fire and a desperate fight ensued, lasting until 10 o'clock. The Indians charged our position three or four times, coming up close enough to hit our men with stones, which they threw by hand. Captain Benteen saw a large mass of Indians gathered on his front to charge, and ordered his men to charge on foot and scatter them.

Benteen led the charge and was upon the Indians before they knew what they were about and killed a great many. They were evidently much surprised at this offensive movement, and I think in desperate fighting Benteen is one of the bravest men I ever saw in a fight. All the time he was going about through the bullets, encouraging the soldiers to stand up to their work and not let the Indians whip them; he went among the horses and pack mules and drove out the men who were skulking there, compelling them to go into the line and do their duty. He never sheltered his own person once during the battle, and I do not see how he escaped being killed. The desperate charging and fighting was over at about one o'clock, but firing was kept up on both sides until late in the afternoon.

Two Moon, interviewed by Hamlin Garland, McClure's Magazine (September, 1898).

While I was sitting on my horse I saw flags come up over the hill to the east like that (he raised his fingertips). Then the soldiers rose all at once, all on horses, like this (he put his fingers behind each other to indicate that Custer appeared marching in columns of fours). They formed into three bunches with a little ways between. Then a bugle sounded, and they all got off horses, and some soldiers led the horses back over the hill.

At last about a hundred men and five horsemen stood on the hill all bunched together. All along the bugler kept blowing his commands. He was very brave too. Then a chief was killed. I hear it was Long Hair (Custer), I don't know; and then five horsemen and the bunch of men, may be so forty, started toward the river. The man on the sorrel horse led them, shouting all the time. He wore a buckskin shirt, and had long black hair and mustache. He fought hard with a big knife. His men were all covered with white dust. I couldn't tell whether they were officers or not. One man all alone ran far down toward the river, then round up over the hill. I thought he was going to escape, but a Sioux fired and hit him in the head. He was the last man. He wore braid on his arms (sergeant).

All the soldiers were now killed, and the bodies were stripped. After that no one could tell which were officers. The bodies were left where they fell. We had no dance that night. We were sorrowful.

Red Horse, interview, Cheyenne River Reservation, 1881...he day was hot. In a short time the soldiers charged the camp. (This was Major Reno's battalion of the Seventh Cavalry.) The soldiers came on the trail made by the Sioux camp in moving, and crossed the Little Bighorn river above where the Sioux crossed, and attacked the lodges farthest up the river. The women and children ran down the Little Bighorn river a short distance into a ravine. The soldiers set fire to the lodges. All the Sioux now charged the soldiers and drove them in confusion across the Little Bighorn river, which was very rapid, and several soldiers were drowned in it. On a hill the soldiers stopped and the Sioux surrounded them. A Sioux man came and said that a different party of Soldiers had all the women and children prisoners. Like a whirlwind the word went around, and the Sioux all heard it and left the soldiers on the hill and went quickly to save the women and children.

From the hill that the soldiers were on to the place where the different soldiers [by this term Red-Horse always means the battalion immediately commanded by General Custer, his mode of distinction being that they were a different body from that first encountered] were seen was level ground with the exception of a creek. Sioux thought the soldiers on the hill [i.e., Reno's battalion] would charge them in rear, but when they did not the Sioux thought the soldiers on the hill were out of cartridges. As soon as we had killed all the different soldiers the Sioux all went back to kill the soldiers on the hill. All the Sioux watched around the hill on which were the soldiers until a Sioux man came and said many walking soldiers were coming near. The coming of the walking soldiers was the saving of the soldiers on the hill. Sioux can not fight the walking soldiers [infantry], being afraid of them, so the Sioux hurriedly left.

The soldiers charged the Sioux camp about noon. The soldiers were divided, one party charging right into the camp. After driving these soldiers across the river, the Sioux charged the different soldiers [i.e., Custer's] below, and drive them in confusion; these soldiers became foolish, many throwing away their guns and raising their hands, saying, "Sioux, pity us; take us prisoners." The Sioux did not take a single soldier prisoner, but killed all of them; none were left alive for even a few minutes. These different soldiers discharged their guns but little. I took a gun and two belts off two dead soldiers; out of one belt two cartridges were gone, out of the other five.

The Sioux took the guns and cartridges off the dead soldiers and went to the hill on which the soldiers were, surrounded and fought them with the guns and cartridges of the dead soldiers. Had the soldiers not divided I think they would have killed many Sioux. The different soldiers that the Sioux killed made five brave stands. Once the Sioux charged right in the midst of the different soldiers and scattered them all, fighting among the soldiers hand to hand.

One band of soldiers was in rear of the Sioux. When this band of soldiers charged, the Sioux fell back, and the Sioux and the soldiers stood facing each other. Then all the Sioux became brave and charged the soldiers. The Sioux went but a short distance before they separated and surrounded the soldiers. I could see the officers riding in front of the soldiers and hear them shooting. Now the Sioux had many killed. The soldiers killed 136 and wounded 160 Sioux. The Sioux killed all these different soldiers in the ravine.

The soldiers charged the Sioux camp farthest up the river. A short time after the different soldiers charged the village below. While the different soldiers and Sioux were fighting together the Sioux chief said, "Sioux men, go watch soldiers on the hill and prevent their joining the different soldiers." The Sioux men took the clothing off the dead and dressed themselves in it. Among the soldiers were white men who were not soldiers. The Sioux dressed in the soldiers' and white men's clothing fought the soldiers on the hill.

The banks of the Little Bighorn river were high, and the Sioux killed many of the soldiers while crossing. The soldiers on the hill dug up the ground [i.e., made earthworks], and the soldiers and Sioux fought at long range, sometimes the Sioux charging close up. The fight continued at long range until a Sioux man saw the walking soldiers coming. When the walking soldiers came near the Sioux became afraid and ran away.

- White Cow Bull said Custer's men charged down Medicine Tail Coulee to the banks of the Little Bighorn (witnessed by: White Man Runs Him, Curley, Pretty Shield, Bobtailed Horse, White Shield, Sitting Bull, Horned Horse, He Dog, Foolish Elk, Peter Thompson, John Martin, Anonymous Sixth Infantry Sergeant)...

- White Cow Bull said three Crow scouts rode to the edge of the bluff above the river and fired down at them (witnessed by Goes Ahead, Hairy Moccasin)...

- White Cow Bull said Custer and his men were hotly pursuing a small band of Indians when they reached the river (witnessed by: Foolish Elk, George Bird Grinnell)...

- White Cow Bull said Custer and his men encountered Indian fire from the other side of the river when they reached the Little Bighorn (witnessed by: Curley, Anonymous Sixth Infantry Sergeant, White Shield)

- White Cow Bull said Custer and his men paused on the far side of the river when they reached the Little Bighorn (witnessed by: Peter Thompson, White Shield)...

- White Cow Bull said after pausing the Americans charged across the Little Bighorn River to attack the Indian village on the other side (witnessed by Curley, Pretty Shield, Horned Horse, Elk Head, Seven Anonymous Hostiles

- White Cow Bull said the ford where Custer tried to cross the Little Bighorn was very thinly defended by the Sioux and Cheyenne (witnessed by: Bobtailed Horse, White Shield, He Dog, Wooden Leg, George Bird Grinnell)...

- White Cow Bull said he was one of the few warriors there when Custer charged into the river and the Indians opened fire (witnessed by: Bobtailed Horse)...

- White Cow Bull said that when the Americans tried to charge across the river at Medicine Tail Coulee, Custer rode at the head of the attack formation with the flag bearer and a "small man on a dark horse," probably half-Sioux interpreter/scout Mitch Bouyer (witnessed by: Pretty Shield)...

- White Cow Bull said a couple Seventh Cavalry troopers were shot out of the saddle and fell in the Little Bighorn before Custer's men could get across the river (witnessed by: Curley, Horned Horse, Pretty Shield, Soldier Wolf, Elk Head, Thomas LaForge, plus Sage, Hollow Horn Eagle and Brave Bird reported wounded American soldiers at the river after the battle, including Mitch Bouyer, the half-Sioux interpreter/scout whom Pretty Shield said rode at Custer's side)...

- White Cow Bull said Custer -- the officer on the "sorrel horse with... four white stockings" -- was one of those shot while crossing the Little Bighorn River (witnessed by: Pretty Shield)...

- White Cow Bull said Custer "fell in the water" of the Little Bighorn River (witnessed by: Pretty Shield)...

- White Cow Bull said Custer's charge at Medicine Tail Coulee was suddenly stopped and repulsed mid-river by the Cheyenne and Sioux defenders (witnessed by: Curley, George Glenn, Jacob Adams)...

I kept riding with the Shahiyelas, still hoping that some of them might tell Meotzi later about my courage. We massed for another charge. The Shahiyela chief, Comes-in-Sight, and a warrior named Contrary Belly [Contrary Big Belly] led us that time. The soldiers' horses were so frightened by all the noise we made that they began to bolt in all directions. The soldiers held their fire while they tried to catch their horses. Just then Yellow Nose rushed in again and grabbed a small flag [guidon] from where the soldiers had stuck it in the ground. He carried it off and counted coup [struck blows] on a soldier with its sharp end. He was proving his courage more by counting that coup than if he had killed the soldier.

Now I saw the soldiers were split into two bands, most of them on foot and shooting as they fell back to higher ground, so we made no more mounted charges. I found cover and began shooting at the soldiers. I was a good shot and had one of the few repeating rifles carried by any of our warriors. It was up to me to use it the best way I could. I kept firing at the two bands of soldiers first at one, then at the other. It was hard to see through the smoke and dust, but I saw five soldiers go down when I shot at them.

Once in a while some warrior showed his courage by making a charge all by himself. I saw one Shahiyela, wearing a spotted war bonnet and a spotted robe of mountain-lion skins, ride out alone.

"He's charging!" someone shouted.

He raced up to the long ridge where the soldiers of one band were making a defense standing there holding their horses and keeping up a steady fire. This Shahiyela charged in almost close enough to touch some of the soldiers and rode around in circles in front of them with bullets kicking up dust all around him. He came galloping back, and we all cheered him.

"Ah! Ah!" he said, meaning "yes" in Shahiyela.

Then he unfastened his belt and opened his robe and shook many spent bullets out on the ground...

The old man grinned at the memory of such courage.

It was a day of bravery -- even for our soldier enemies. They all fought well and died in courage, except for one soldier on a sorrel horse. He broke away from the others and started riding off down the ridge. Two Shahiyelas and a Lakota chased after him, shooting at him as they rode. But the soldier's horse was fast and they couldn't catch him. I saw him yank out his revolver and thought he was going to shoot back at these warriors. Instead he put the revolver to his head, pulled the trigger, and fell dead.

This may have been 2nd Lieutenant Henry M. Harrington, C. Company, whose body was never identified. [Note: It is remotely possible that this suicide could also have been Custer himself. For more info on American suicides, see Who Killed Custer -- The Eye-witness Answer.]

In a little while all my bullets were gone. But by that time the soldiers lay still. We had killed them all. The battle was over. Soon we were shouting victory yells. When the women and children heard us, they came out on the ridge to strip the bodies and catch some of the big horses the soldiers had ridden. Some women had lost husbands or brothers or sons in the fight, so they butchered the soldiers' bodies to show their grief and anger.

I began looking for bullets and weapons in the piles of dead bodies. Near the top of the ridge I saw a naked body and turned it over. The face had little hairs on it and looked like the white man who had worn the buckskin jacket and had lired at me across the ford -- the same one I had shot off his horse. I remembered how close some of his bullets had come, so I thought I would take the medicine of his trigger finger to make me an even better shot. Taking out my knife. I began to cut off that finger.

Just then I heard a woman's voice behind me. I turned to see Meotzi and Yellow Bird and an older Shahiyela woman standing there. The older woman pointed to the while man's body, saying:

"He is our relative."

Then she signed for me to go away. I looked at Meotxi then and smiled, but she didn’t smile back at me, so I wondered if she thought it was wrong for a warrior to be cutting on an enemy's body. I decided she wouldn't be as proud of me if I cut off the white man's finger, and moved away. Pretending to be busy looking for bullets, I glanced back. Meotxi was looking down at the body while the older woman poked her sewing awl deep into each of the white man's ears. I heard her say:

"So Long Hair will hear better in the Spirit Land."

[Note: Cheyenne youth Dives Backward witnessed this scene -- a warrior trying to cut a finger off a dead American who was driven away by two grieving squaws, one Monaseetah and one an old woman with an awl.]

That was the first I knew that Long Hair was the soldier chief we had been fighting and the white man I had shot at the ford...

During this time the warriors were seen riding out of the village by hundreds, deploying across his front to his left, as if with the intention of crossing the stream on his right, while the women and children were seen hastening out of the village in large numbers in the opposite direction.

During the fight at this point Curley saw two of Custer's men killed, who fell into the stream. After fighting a few moments here, Custer seemed to be convinced that it was impracticable to cross, as it only could be done in column of fours exposed during the movement to a heavy fire from the front and both flanks. He therefore ordered the head of the column to the right, and bore diagonally into the hills, downstream, his men on foot leading their horses. In the meantime the Indians had crossed the river (below) in immense numbers, and began to appear on his right flank and in his rear; and he had proceeded but a few hundred yards in the direction the column had taken, when it became necessary to renew the fight with the Indians who had crossed the stream.

At first the command remained together, but after some minutes' fighting, it was divided, a portion deployed circularly to the left, and the remainder similarly to the right, so that when the line was formed, it bore a rude resemblance to a circle, advantage being taken as far as possible of the protection afforded by the ground. The horses were in the rear, the men on the line being dismounted, fighting on foot. Of the incidents of the fight in other parts of the field than his own, Curley is not well informed, as he was himself concealed in a ravine, from which but a small portion of the field was visible.

The fight appears to have begun, from Curley's description of the situation of the sun, about 2:30 or 3 o'clock p.m., and continued without intermission until nearly sunset. The Indians had completely surrounded the command, leaving their horses in ravines well to the rear, themselves pressing forward to attack on foot. Confident in the superiority of their numbers, they made several charges on all points of Custer's line, but the troops held their position firmly, and delivered a heavy fire, and every time drove them back. Curley said the firing was more rapid than anything he had ever conceived of, being a continuous roll, as he expressed it, "the snapping of the threads in the tearing of a blanket. The troops expended all the ammunition in their belts, and then sought their horses for the reserve ammunition carried in their saddle pockets.

As long as their ammunition held out, the troops, though losing considerable in the fight, maintained their position in spite of the efforts of the Sioux. From the weakening of their fire toward the close of the afternoon, the Indians appeared to believe their ammunition was about exhausted, and they made a grand final charge, in the course of which the last of the command was destroyed, the men being shot where they lay in their position in the line, at such close quarters that many were killed with arrows. Curley says that Custer remained alive through the greater part of the engagement, animating his men to determined resistance; but about an hour before the close of the fight, he received a mortal wound.

Curley says the field was thickly strewn with dead bodies of the Sioux who fell in the attack, in number considerably more than the force of soldiers engaged. He is satisfied that their loss will exceed six hundred killed, beside an immense number wounded.

Curley accomplished his escape by drawing his blanket around him in the manner of the Sioux and passing through an interval which had been made in their lines as they scattered over the field in their final charge. He says they must have seen him, for he was in plain view, but was probably mistaken by the Sioux for one of their number, or one of their allied Arapahos or Cheyennes.

As long as their ammunition held out, the troops, though losing considerably in the fight, maintained their position in spite of all the efforts of the Sioux. From the weakening of their fire toward the close of the afternoon the Indians appeared to believe that their ammunition was about exhausted, and they made a grand final charge, in the course of which the last of the command was destroyed, the men being shot where they lay in their positions in the line, at such close quarters that many were killed with arrows. Curley said that Custer remained alive throughout the greater part of the engagement, animating his men to determined resistance, but about an hour before the close of the fight lie received a mortal wound.

After sun-down that night I slipped through the Indian line and swung around towards the north, and the next morning at day-break I was down where the Little Horn flows into the Bighorn River. There were some soldiers there (General Terry's) and their leader was an officer whom the Indians called "Man Without Hip" or "Lame Hip" (General Terry) and another officer whom the Indians called "White Whiskers" (General Gibbon). I told them all I knew about the fight, and that my clothes were worn out. I had no moccasins, so I was going home. The officers said all right and I rode on. I went to Pryor where the Crows were camped. When I came into camp, some of the Crows thought I was a Sioux and commenced shooting at me.

I have heard many people say that Curley was the only survivor of this battle, but Curley was not in the battle. Just about the time Reno attacked the village, Curley with some Arikara scouts ran off a big band of Sioux ponies and rode away with them. Some of the Arikaras, whom I met afterwards, told me that Curley went with them as far as the Junction (where the Rosebud joins the Yellowstone River). I did not see Curley again until the next fall, when I met him up on the Yellowstone in the camp of the Mountain Crows, so Curley did not see much of the battle....

Two Moons said he saw soldiers “drop into the river-bed like buffalo fleeing.” The Minneconjou warrior Red Horse said several troops drowned. Many of the Indians charged across the river after the soldiers and chased them as they raced up the bluffs toward a hill (now known as Reno Hill, for the major who led the soldiers). White Eagle, the son of Oglala chief Horned Horse, was killed in the chase. A soldier stopped just long enough to scalp him—one quick circle-cut with a sharp knife, then a yank on a fistful of hair to rip the skin loose.

Another son of Horned Horse, White Cow Walking, survived the battle. [His] brother [was] scalped and killed by Reno [soldiers]. [He did] not [fight] beside Sitting Bull,

The warriors ran at once for their arms, but by the time they had taken up their guns and ammunition belts, the soldiers had disappeared. The Indians thought they had been frightened off by the evident strength of the village, but again, after what seemed quite a long interval, the head of Custer's column showed itself coming down a dry watercourse, which formed a narrow ravine, toward the river's edge. He made a dash to get across, but was met by such a tremendous fire from the repeating rifles of the savages that the head of his command reeled back toward the bluffs after losing several men who tumbled into the water, which was there but eighteen inches deep, and were swallowed up in the quicksand. This is considered an explanation of the disappearance of Lieutenant Harrington and several men whose bodies were not found on the field of battle. They were not made prisoners by the Indians, nor did any of them succeed in breaking through the thick array of infuriated savages. [Note: This is a novel theory concerning the quicksand at Medicine Tail Coulee and the complete disappearance of some of the fallen Seventh Cavalry troopers. Horned Horse's supposition that Custer's men were turned back by large numbers of Indian defenders at Medicine Tail Coulee is contradicted by White Shield, He Dog and others. More likely, Custer's charge was repulsed by the one shot from one defender, White Cow Bull, who described shooting a man who can only be Custer off his horse and watching the man fall in the river, which brought all the other cavalry troopers to an immediate halt. See Who killed Custer -- The Eye-witness Answer for more info.]

Horned Horse did not recognize Custer, but supposed he was the officer who led the column that attempted to cross the stream. Custer then sought to lead his men up to the bluffs by a diagonal movement, all of them having dismounted, and firing, whenever they could, over the backs of their horses at the Indians, who by that time had crossed the river in thousands, mostly on foot, and had taken the General in flank and rear, while others annoyed him by a galling fire from across the river.

Hemmed in on all sides, the troops fought steadily, but the fire of the enemy was so close and rapid that they melted like snow before it, and fell dead among their horses in heaps. He could not tell how long the fight lasted, but it took considerable time to kill all the soldiers. The firing was continued until the last man of Custer's command was dead. Several other bodies besides that of Custer remained unscalped, because the warriors had grown weary of the slaughter. The watercourse, in which most of the soldiers died, ran with blood. He had seen many massacres, but nothing to equal that.

If the troops had not been encumbered by their horses, which plunged, reared, and kicked under the appalling fire of the Sioux, they might have done better. As it was, a great number of Indians fell, the soldiers using their revolvers at close range with deadly effect. More Indians died by the pistol than by the carbine. The latter weapon was always faulty.

It "leaded" easily and the cartridge shells stuck in the breech the moment it became heated, owing to some defect in the ejector....

The whites had the worst of it. More than 30 were killed before they reached the top of the hill and dismounted to make a stand. Among the bodies of men and horses left on the flat by the river below were two wounded Ree scouts. The Oglala Red Hawk said later that “the Indians [who found the scouts] said these Indians wanted to die—that was what they were scouting with the soldiers for; so they killed them and scalped them.”

The Yanktonais White Thunder said he saw the second group make a move toward the river south of the ford by the Cheyenne camp, then turn back on reaching “a steep cut bank which they could not get down.” While the soldiers retraced their steps, White Thunder and some of his friends went east up and over the high ground to the other side, where they were soon joined by many other Indians. In effect, White Thunder said, the second group of soldiers had been surrounded even before they began to fight.

From the spot where the first group of soldiers retreated across the river to the next crossing place at the northern end of the big camp was about three miles—roughly a 20-minute ride. Between the two crossings steep bluffs blocked much of the river’s eastern bank, but just beyond the Cheyenne camp was an open stretch of several hundred yards, which later was called Minneconjou Ford. It was here, Indians say, that the second group of soldiers came closest to the river and to the Indian camp. By most Indian accounts it wasn’t very close.

Approaching the ford at an angle from the high ground to the southeast was a dry creek bed in a shallow ravine now known as Medicine Tail Coulee. The exact sequence of events is difficult to establish, but it seems likely that the first sighting of soldiers at the upper end of Medicine Tail Coulee occurred at about 4 o’clock, just as the first group of soldiers was making its dash up the bluffs toward Reno Hill and Crazy Horse and his followers were turning back. Two Moons was in the Cheyenne camp when he spotted soldiers coming over an intervening ridge and descending toward the river.

Most of the men under Custer's second in command, Major Marcus Reno, made it out alive, held together over three horrible days of combat and thirst. Yet, in the public's opinion, Reno was a coward.

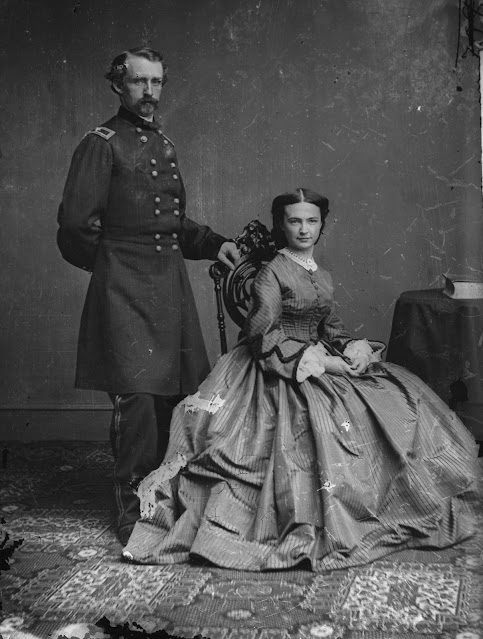

The results for the U.S. Army were even worse in the Second Battle of the Little Big Horn, when, for fifty-seven years, they were mercilessly attacked by a five foot four inch Victorian widow with blue-gray eyes and chestnut hair. Her name was Elizabeth Bacon Custer (above). And in this engagement she wiped the U.S. Army out, leaving no survivors - least of all, Marcus Reno, whom she blamed for her husband's death.

Immediately after the battle the military judgments were fairly unanimous. President Grant, who had been elevated to the White House based on his record as a military commander, told a reporter, “I regard Custer’s massacre as a sacrifice of troops brought on by Custer himself,…(which) was wholly unnecessary – wholly unnecessary.” General Philip Sheridan, the man who had lobbied for Custer’s inclusion on the expedition considered the disaster primarily Custer’s fault. “Had the Seventh Cavalry been held together, it would have been able to handle the Indians on the Little Big Horn."

Immediately after the battle the military judgments were fairly unanimous. President Grant, who had been elevated to the White House based on his record as a military commander, told a reporter, “I regard Custer’s massacre as a sacrifice of troops brought on by Custer himself,…(which) was wholly unnecessary – wholly unnecessary.” General Philip Sheridan, the man who had lobbied for Custer’s inclusion on the expedition considered the disaster primarily Custer’s fault. “Had the Seventh Cavalry been held together, it would have been able to handle the Indians on the Little Big Horn."

Having dismissed Custer, the army also dismissed his 34 year old widow. Barely a month after her husband had died amid the Montana scrub brush, “Libby” Custer was forced to leave Fort Abraham Lincoln. As a widow Libby had no right to quarters on the post, and so lost the social support of her Army life and fellow wives. Her income was immediately reduced to the widow’s pension of $30 a month; her total assets were worth barely $8,000, while the claims against Custer’s estate exceeded $13,000. And then, in her hour of need, Libby received support from an unexpected source.

Having dismissed Custer, the army also dismissed his 34 year old widow. Barely a month after her husband had died amid the Montana scrub brush, “Libby” Custer was forced to leave Fort Abraham Lincoln. As a widow Libby had no right to quarters on the post, and so lost the social support of her Army life and fellow wives. Her income was immediately reduced to the widow’s pension of $30 a month; her total assets were worth barely $8,000, while the claims against Custer’s estate exceeded $13,000. And then, in her hour of need, Libby received support from an unexpected source. His name was Frederick Whittaker, and he scratched out a living as a writer of pulp fiction and non-fiction for magazines of the day, “…about the best of its kind”. He had met Custer during the Civil War, and the General’s death inspired him to write a dramatic eulogy praising the fallen hero in Galaxy Magazine. Whittaker also mentioned Custer’s “natural recklessness and vanity”, but Libby immediately contacted him. Libby provided Whittaker with the couple’s personal letters, access to family and friends, war department correspondence and permission to use large sections from Custer’s own book, “My Life on the Plains.”

His name was Frederick Whittaker, and he scratched out a living as a writer of pulp fiction and non-fiction for magazines of the day, “…about the best of its kind”. He had met Custer during the Civil War, and the General’s death inspired him to write a dramatic eulogy praising the fallen hero in Galaxy Magazine. Whittaker also mentioned Custer’s “natural recklessness and vanity”, but Libby immediately contacted him. Libby provided Whittaker with the couple’s personal letters, access to family and friends, war department correspondence and permission to use large sections from Custer’s own book, “My Life on the Plains.”

This time there was no hint of faults in Custer. Instead the blame was laid elsewhere. Of Custer, Whittaker wrote; “He could have run like Reno had he wished...It is clear, in the light of Custer’s previous character, that he held on to the last, expecting to be supported, as he had a right to expect. It was only when he clearly saw he had been betrayed, that he resolved to die game, as it was too late to retreat.” http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/History.Whittaker (Sheldon and Company, New York, 1876).

This time there was no hint of faults in Custer. Instead the blame was laid elsewhere. Of Custer, Whittaker wrote; “He could have run like Reno had he wished...It is clear, in the light of Custer’s previous character, that he held on to the last, expecting to be supported, as he had a right to expect. It was only when he clearly saw he had been betrayed, that he resolved to die game, as it was too late to retreat.” http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/History.Whittaker (Sheldon and Company, New York, 1876). All but a few professional soldiers admitted that Whittaker had gotten it wrong. In fact one of the most serious charges laid against Custer while he had been alive was that at the Washita he had, in fact, deserted a junior commander and his men. But those same officers now withheld their criticism of Whittaker to avoid being forced to also criticize Custer's widow. Reno (above) eventually was forced to ask for and received a Court of Inquiry (not a Court Martial) on his conduct at Little Big Horn, which cleared his name and revealed the character of the people Whittaker had relied on for his version of the battle. But it made little difference to the general public, which declared the Inquiry a whitewash.

All but a few professional soldiers admitted that Whittaker had gotten it wrong. In fact one of the most serious charges laid against Custer while he had been alive was that at the Washita he had, in fact, deserted a junior commander and his men. But those same officers now withheld their criticism of Whittaker to avoid being forced to also criticize Custer's widow. Reno (above) eventually was forced to ask for and received a Court of Inquiry (not a Court Martial) on his conduct at Little Big Horn, which cleared his name and revealed the character of the people Whittaker had relied on for his version of the battle. But it made little difference to the general public, which declared the Inquiry a whitewash. Elizabeth Custer went on to support herself comfortably by writing three books; “Tenting on the Plains”,"Following the Guidon” and “Boots and Saddles”. In each her husband was idolized and lionized. In 1901 she managed to squeeze out one more, a children’s book, “The Boy General. Story of the Life of Major-General George A. Custer”: “The true soldier asks no questions; he obeys, and Custer was a true soldier. He gave his life in carrying out the orders of his commanding general… He had trained and exhorted his men and officers to loyalty, and with one exception they stood true to their trust, as was shown by the order in which they fell.” By the time Libby died, in 1933, at the age of ninety-one, her vision of Little Big Horn was set in the concrete of the printed page.

Elizabeth Custer went on to support herself comfortably by writing three books; “Tenting on the Plains”,"Following the Guidon” and “Boots and Saddles”. In each her husband was idolized and lionized. In 1901 she managed to squeeze out one more, a children’s book, “The Boy General. Story of the Life of Major-General George A. Custer”: “The true soldier asks no questions; he obeys, and Custer was a true soldier. He gave his life in carrying out the orders of his commanding general… He had trained and exhorted his men and officers to loyalty, and with one exception they stood true to their trust, as was shown by the order in which they fell.” By the time Libby died, in 1933, at the age of ninety-one, her vision of Little Big Horn was set in the concrete of the printed page. The first who endorsed Libby's view was Edward S. Godfrey, who had been a junior officer at the Little Big Horn and a Custer “fan” from before the battle. His 1892 “Custer’s Last Battle” was unequivocal. “...had Reno made his charge as ordered,…the Hostiles would have been so engaged… that Custer’s approach…would have broken the moral of the warriors….(Reno’s) faltering ...his halting, his falling back to the defensive position in the woods...; his conduct up to and during the siege…was not such as to inspire confidence or even respect,…” .” These attacks on Reno continued for most of the 20th century. The 1941 movie staring Errol Flynn as Custer displays Libby's view of Reno as well as any tome, echoed even by respected historians such as Robert Utley who in the 1980’s described Reno as "… a besotted, socially inept mediocrity, (who) commanded little respect in the regiment and was the antithesis of the electric Custer in almost every way.”

The first who endorsed Libby's view was Edward S. Godfrey, who had been a junior officer at the Little Big Horn and a Custer “fan” from before the battle. His 1892 “Custer’s Last Battle” was unequivocal. “...had Reno made his charge as ordered,…the Hostiles would have been so engaged… that Custer’s approach…would have broken the moral of the warriors….(Reno’s) faltering ...his halting, his falling back to the defensive position in the woods...; his conduct up to and during the siege…was not such as to inspire confidence or even respect,…” .” These attacks on Reno continued for most of the 20th century. The 1941 movie staring Errol Flynn as Custer displays Libby's view of Reno as well as any tome, echoed even by respected historians such as Robert Utley who in the 1980’s described Reno as "… a besotted, socially inept mediocrity, (who) commanded little respect in the regiment and was the antithesis of the electric Custer in almost every way.” So for over a century Marcus Reno was reviled and despised as the coward who did not charge as ordered, instead pleading weasel-like that Custer had not supported him as promised. It would not be until Ronald Nichols biography of Reno, “In Custer’s Shadow” (U. of Oklahoma Press, 1999) that Reno received a fair hearing.

So for over a century Marcus Reno was reviled and despised as the coward who did not charge as ordered, instead pleading weasel-like that Custer had not supported him as promised. It would not be until Ronald Nichols biography of Reno, “In Custer’s Shadow” (U. of Oklahoma Press, 1999) that Reno received a fair hearing. About the same time the Indian accounts of the fight began to finally be given a serious consideration by white historians, including the story told to photographer Edward Curtis in 1907 by three of Custer’s Indian scouts. The three men said they watched amazed as Custer stood on the bluffs overlooking Reno’s fight in the valley, a story supported by some soldiers in the valley fight who reported seeing Custer on the bluffs. (Most historians had always assumed they were imagining things.)

About the same time the Indian accounts of the fight began to finally be given a serious consideration by white historians, including the story told to photographer Edward Curtis in 1907 by three of Custer’s Indian scouts. The three men said they watched amazed as Custer stood on the bluffs overlooking Reno’s fight in the valley, a story supported by some soldiers in the valley fight who reported seeing Custer on the bluffs. (Most historians had always assumed they were imagining things.)

And it did. But sure was a long time coming.

And it did. But sure was a long time coming.